So it is SpaceX that kicks off the launches of the year 2018 with a flight of a new Falcon 9. The launcher took off on January 8th at 2:00 AM (French time) with… Zuma! This somewhat special satellite was successfully placed into orbit by the private American company.

Zuma is a highly secretive satellite: we really know nothing about it unlike other secret launches such as the NROL or X-37B missions, which reveal some information. Indeed, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) communicates minimally about their satellites by giving a mission number like NROL-42 or NROL-76 (the latter was actually launched by SpaceX in mid-2017), which leads us to legitimately doubt whether Zuma was commissioned by the NRO. And indeed, we do not even know the origin of this order: the only point that escapes the mystery is the satellite’s manufacturer, Northrop Grumman. You can see in the images here and below that only this company name appears on the fairing.

Northrop Grumman is an American company that produces satellites, as well as missiles and military aircraft for the US Air Force. Therefore, it was this agency that manufactured Zuma and arranged the purchase of the Falcon 9 launch. However, the big unknown remains the entity that will benefit from this satellite. It is possible, even probable, that this satellite is involved in government security. Another known aspect of the mission is its final orbit. We know that the satellite was launched into a so-called low orbit, meaning it orbits at an average altitude of about 1,900km.

Its orbit is also inclined at approximately 50° relative to the equatorial plane. This inclination is reminiscent of that of the International Space Station, but the similarities end there, as the ISS is located only 400km above Earth. It is also known that this orbit does not need to be perfect. Indeed, the launch window for the Falcon 9 lasted two hours (from 1:00 to 3:00). This long launch window contrasts with shorter launch windows for other flights, such as the Dragon CRS-13 cargo mission, for which the window did not exceed one second.

Speaking of time, the launch of the Zuma satellite was postponed numerous times. It was supposed to take off on November 16, 2017, from Launch Pad 39A at Cape Canaveral. Unfortunately, high-altitude winds were detected, and the flight was postponed by 24 hours. The next day, there was a problem with the fairing: one of the telemetry values was incorrect. Another deadline! On the 18th, the problem still wasn’t resolved, and SpaceX announced a postponement until further notice, and during the day, the launcher was returned to the hangar. A funny fact, SpaceX had never launched rockets during the month of November, and this one was supposed to be the first: as you guessed, the curse continues, and to this day, no Falcon 9 has taken off during the month of November.

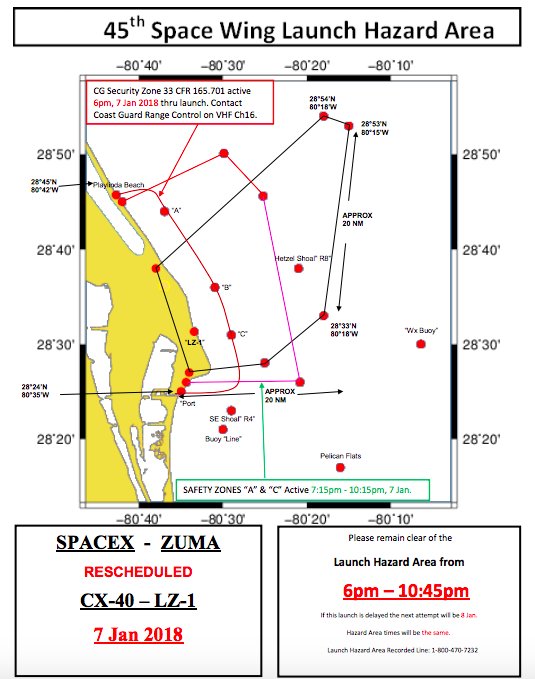

The postponement pushed the launch to early January, and it was on the 3rd that we saw the booster coming out of the hangar. Only the first stage of the launcher was taken out to go to Launch Pad SLC-40. This launch pad had been brought back into service during this long waiting phase, following the accident of an explosive Static Fire, and had only experienced one flight before this launch: that of the CRS-13 cargo mission. On January 3rd, the booster underwent a WDR test, which involves filling the booster with fuel to check the integrity of the stage. The Static Fire for this launch had already been conducted in November, during the initial launch campaign. Another fueling test was required two days later due to the postponement from the 6th to the 7th of January, due to new high-altitude winds, finally taking off on January 8, 2018.

During the live broadcast, we only received information about the first stage, which is logical for a secret flight that only leaks non-essential or easily determinable information. After propelling the second stage and the fairing, the booster returned to Cape Canaveral and landed on the LZ-1 area. This return occurred in three main stages: just after the separation of the second stage, the booster flipped and ignited three of its nine engines to modify its trajectory and return to LZ-1. A few minutes later (as you can see on the timeline below), the stage performed another ignition to slow down and avoid excessive heating during re-entry. Finally, a single engine was reignited for the final braking and smooth landing. These three ignitions are respectively called Boostback burn, Entry burn, and Landing burn.

SpaceX announced that the flight was a success, and the first stage was recovered without any issues! This flight heralds a promising year for space exploration in 2018!

Photos of the launch: